Redefining the American Dream: Implications for Architecture and Design

Expensive homes, car-dependent infrastructure, and overregulation are forcing young Americans to reevaluate the vision of the American Dream. What impact will it have on the future of design?

During the post-COVID travel boom, millions of young Americans vacationed (or worked remotely) in Europe and Asia, eventually coming back to the United States with a single question:

“Why can’t we have this here?”

The this in question is the experience that defines most major, non-American cities: accessible public transportation; dense, mixed-use housing; and a high quality of living (e.g. affordable transportation, high quality restaurants). This slightly overgeneralized view of cities outside of the United States has become a rallying cry for young Americans that want to renegotiate the definition and outcome of the American Dream1.

Unlike their predecessors, who would visit these first-rate non-American cities and return to their suburban homes with pretty postcards and fridge magnets—younger Americans have come back to their rickety, overpriced apartments with a deep sense of dissatisfaction. They were promised a future that not only is out of reach for the vast majority of them, but one that they saw led to atomized, unhappy communities that became self-obsessed with stupid things—like having a two-door garage and a luscious front yard to impress the neighbors.

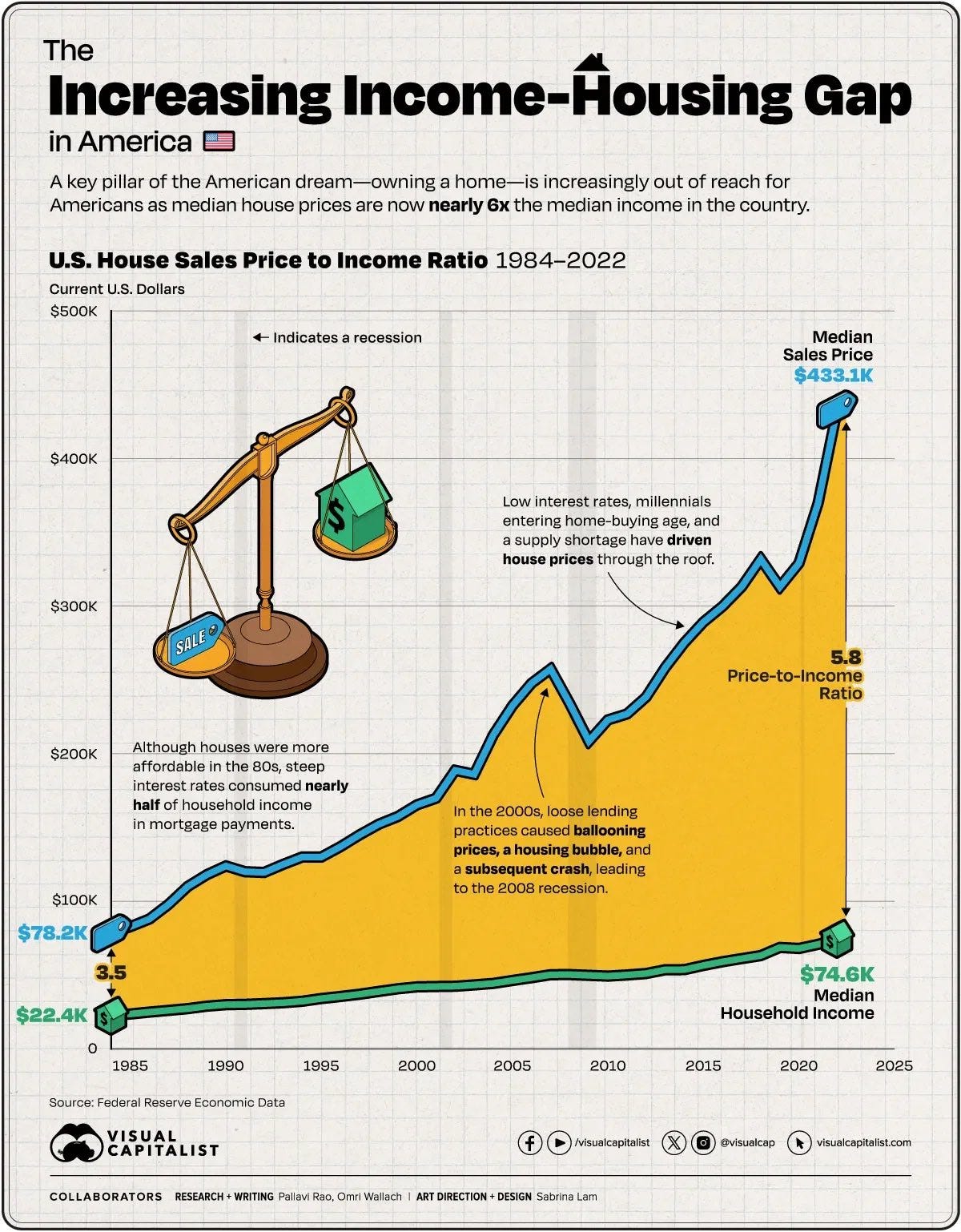

The financial argument for the American Dream: invest in a home and see it go up in value—was irrevocably damaged after 2008, where millions of Americans’ investments (their mortgages) spiked and led to foreclosures, evictions, and homelessness. Furthermore, the post-pandemic boom in real estate has cemented the fact that even if homes do increase in value, they can only go so high until the next generation cannot afford to buy in. What message is being sent to younger Americans when starter homes bought with 6 months starting salary in 1970 go on sale in 2025 for millions of dollars, requiring years of hard work just to afford a down payment?2

Lastly, the decay of US prestige, institutions, and overall quality of life is leading younger, action-oriented Americans to copy things they see abroad. Why are cities like Tokyo or Paris so easy to get around, and always seem to have a cafe or bistro right around the corner, eliminating the need to drive everywhere? This simple desire of wanting to live in towns and cities that prioritize the quality of life of its residents, rather than inefficient modes of transportation (such as cars) is reshaping the American Dream.

In short, the American Dream of home ownership is being transferred from the suburbs to the towns and cities, where good public infrastructure and dense building design can regenerate a sense of community that was lost in the gray landscapes of American suburbia life—and reintroduce housing that is more affordable to new homebuyers. This generational sea change is already rippling across America, and will rewrite how housing is designed, built, regulated, and formalized as an aesthetic this pushes American society into the 21st century3.

The pendulum of history swings against NIMBYism

NIMBY, or not-in-my-backyard movement, was started in the 80s by homeowners that opposed real estate or infrastructure development in their neighborhoods. Partly due to wanting to keep their neighborhood as is and mostly wanting to keep their home value high, NIMBY’s are a big reason there is such a demand for affordable high-density housing today.

The YIMBY movement (yes-in-my-backyard) has exploded onto the scene in the past few years as a response to NIMBYs stranglehold on housing regulations and real estate development. Taking on a grass-roots approach, local YIMBY groups have begun reversing NIMBY-era regulations in states like Texas.

YIMBY proponents, themselves overwhelmingly Millennials, understand that the cost, aesthetic, and planning issues in modern housing are mainly due to regulations that constrain the ability of developers to effectively make money while making a building that is aesthetically appealing. This system view of the issue at hand has enabled YIMBY advocates to simultaneously push new laws that promote the building of new housing, the creation of new public transportation projects, and the reintroduction of mixed zoning.

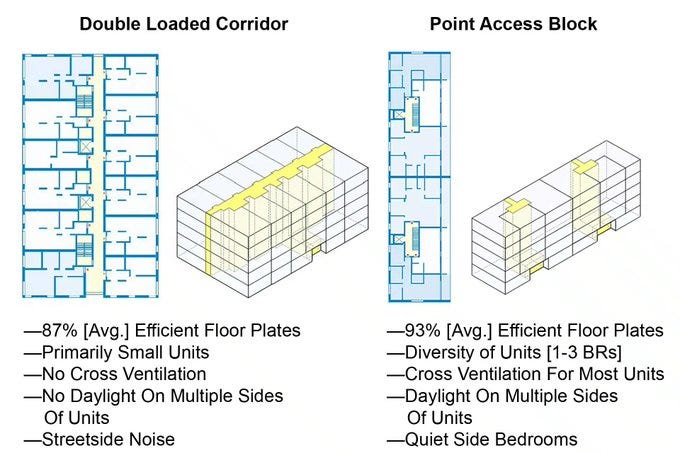

YIMBY advocates are also pushing for changes in US building codes, which are broadly understood to be far too restrictive and biased towards car-dependent infrastructure (a leftover of the 1960s). One may not realize it, but simple things, like the sizes of elevators, parking requirements, or the distance between the street and a building have a massive effect on how housing is designed, built, and sold.

Deregulation is the name of the game

A big reason why new 5-over-1s look the way they do today is due to the regulatory burden developers encounter when building high-density housing. In order to satisfy regulatory demand and make a profit, builders are resorting to building ‘luxury apartments’, which comp out at higher rates than smaller, denser apartments4.

These vinyl monstrosities house fewer people than older, equivalent buildings, are built more cheaply, and include quick-to-install amenities that artificially balloon the cost of rent for residents. These new builds are cropping all around the country, yet will see falling demand as most young Americans are priced out of these new developments5.

Simple things, like eliminating 2-stairway requirements, will increase the amount of units that can be included in a new build and dramatically make housing more affordable.

Lastly, the reintroduction of mixed-use housing will help reinvigorate local communities by creating new job opportunities, lower commute times, and improve quality of life overall. A big reason why quality of life appears higher in cities like Paris and Tokyo is due to their commitment to mixed zoning laws, where small businesses can operate on the first floor of a residential building—lessening the need for cars and car-dependent infrastructure.

Aesthetic revitalization of the city

Much of the deregulation that younger Americans and YIMBYists are advocating for comes from a dissatisfaction with modern aesthetic standards in buildings. Regulations and budget—to a large extent—restrict the architect’s ability to create aesthetically appealing buildings. There is now a broad understanding that building aesthetics have a direct correlation with overall happiness and quality of life—and that a building’s value goes beyond square footage and built-in amenities.

As a result, we’ve seen a been a desire to re-introduce classical architecture (e.g. federalist and Haussmann style) in high density housing. This addresses the aesthetic gap we’ve seen in modern builds, which look more like Holiday Inns than actual apartments or homes. Of course, the average person may not think they care which their building looks like, but designers and architects know that aesthetics have a deep effect on how buildings are perceived, used, and treated.

Materiality and texture will define new builds because they make the living space feel real when compared to the grey boxes we’ve been building for 30 years. Stone, brickwork, thermally-treated wood, and tile are making a comeback in modern new builds—attracting tenants that to live in buildings that have soul and are built of local materials. Many new builds that embody this use of local materials and textures can be found in Iran (of all places). These projects have been a great source of inspiration to US-based designers and architects that want to use more durable materials in high-density housing.

So where do we go from here?

Although the traditional American Dream is not dead (there are still plenty of people that want a McMansion in the suburbs), it certainly is morphing into a version that better fits the reality of American Millennials and Zoomers—A reality where homeownership isn’t the key to succeeding at life, but rather a piece of a fulfilling lifestyle. This more holistic view at life will have deep implications for designers and architects, who will have to consider not just how a building is built, but how public infrastructure, walkable spaces, and mixed-zoning opportunities create a complete offering that exemplifies this new American Dream.

Although this future will expand the responsibilities and work of the designer/architect, it should be understood that no object or building lives in a vacuum: More emphasis on understanding the relationships between buildings, cities, and residents will generate better designs that will serve society as a whole. Although the United States is behind the world in having truly dense, modern cities—one cannot discount the Americans’ world-renowned capacity to enact change.

You can follow me on X a DesignInReach. I will be posting more content on there as I get back to posting regularly on Substack.

Unaffordable housing is pushing the generational trend of investing in non-physical assets, such as crypto or the stock market. This lower appetite for buying real estate will put pressure on Baby Boomers that are now looking to finance their retirements with the sale of their real estate assets.

The change is also being observed in parts of Europe that have many of the same housing and infrastructure issues that plague the US.

This issue is analogous to how American cars after 2012 have become larger, more expensive, and less fuel efficient overall. EPA regulations made it illegal to make cars that were under a certain size-to-fuel-consumption curve—hence why all new cars we see on the road are mid-sized SUV with stickers prices starting at $40,000.

If things weren’t bad enough, a lot of luxury apartment builds are being built on the assumption that older Gen X and Boomer parents will be buying these properties and housing their children with them. This only highlights the issue and does nothing to solve it.